Transhumanism and the politics of Akira

A blessed Feast of the Nativity to one and all! Christ is Born!

I thought I would do something special on Paneurasianist for the holiday, so I decided to go back, rewatch and review one of my all-time favourites from college days, the wild-ride behemoth that is Ôtomo Katsuhiro’s Akira. It’s actually fairly hard to review this movie without resorting to the usual breathless superlatives – ‘indispensable’, ‘iconic’, ‘landmark’, ‘definitive’, ‘masterpiece’, ‘monolith’, ‘tour de force’ – in part because they are all so thoroughly deserved. Let’s face it. Even thirty years later Akira is still cool af, still top of its class for its medium, and how. I also want to use the opportunity to touch a bit on both the leftist class politics of Akira and the rather pessimistic attitude the film takes toward transhumanist tinkering. In retrospect it seems oddly fitting that I should use the day we commemorate God becoming man in the flesh, to review a film that casts a dim view on ill-begotten attempts by man to outgrow the flesh and become a god.

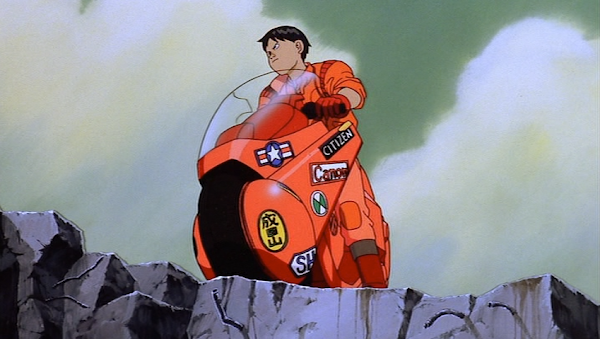

First off, let’s start off with the æsthetics. Akira basically made animated cyberpunk the same way Blade Runner made live-action cinematic cyberpunk. Glittering, monolithic, towering skyscrapers awash in neon and floodlights above; slums, industrial wreckage, drug abuse, protest, human suffering and violence below – in other words, high tech and low life. The fascination with, in particular, motorbikes in Japanese cyberpunk is very much attributable to Kaneda’s hot-red custom ride. The chase sequence with the flying bikes with minigun mounts in the sewers under the defence ministry is also something of a defining moment in the medium. It helps drastically that the quality of the animation is also seamless: the carefully-weighted articulation which made ‘Construction Cancellation Order’ such a work of art has here been honed to a knife’s-edge. Every single scowl, grimace, swagger, stumble and hand gesture is beautifully rendered, giving the animation a realism and weight that few other features have ever attained. Ôtomo’s broad faces with their small yet instantly-expressive features demonstrate almost better than anything else that this is a hard-knock universe. Although, if you’re ever in doubt of that: there’s also the Peckinpah- and Tarantino-level gratuities of face-meets-asphalt blood spatter, gaping bullet wounds and various forms of technologically-assisted bodily dismemberment (not to mention a great heaping portion of cybernetic body horror toward the end) to remind you of the fact.

Ôtomo Katsuhiro’s premise in Akira is subtle and complex, and he sprawls it with overwhelming conviction into a vast epic. But at the core of it is this: what would happen if you took a callow, insecure wannabe member of a biker gang, and suddenly gave him godlike psionic powers and near-omnipotence? Answer: nothing good. Shima Tetsuo is the ‘runt’ of the Capsules, looked after and protected – with a certain degree of condescension – by the head of the gang, Kaneda Shôtarô. The Capsules are duking it out on their bikes with a rival gang, the Clowns, on the streets of Neo Tôkyô… which has been rebuilt after a mass disaster took out most of the city following World War III. At the same time, anti-austerity protests have broken out in response to a neoliberal ‘tax reform’ floated by the Japanese government, resulting in skyrocketing unemployment and general social misery (sound familiar?). A radical element among the protesters has somehow gotten hold of Takashi, a little boy who looks like an old man, whose very existence is supposed to be a carefully-guarded state secret. Tetsuo very literally nearly runs Takashi down, and along with the rest of the Capsules, is taken into police custody. Very soon after his encounter with Takashi, Tetsuo begins experiencing headaches and visions of someone named ‘Akira’, and he begins to manifest powerful psychic abilities. After Tetsuo escapes from captivity, a race begins. The military, led by the brutal Col Shikishima, wants to stop him. The scientists, chiefly Dr Ônishi, want to study him. And Kaneda, who joins up with the radicals after encountering the attractive Kei, wants to save him.

It’s a tribute to Ôtomo’s remarkable storytelling ability that the plot of Akira is actually a great deal more complex than this, and involves a number of diverging and overlapping storylines, yet at no point does the film feel cluttered or overwrought, and the viewer is never placed at a loss as to what is going on or why. The set pieces are all wonderfully designed and immersively detailed. These include the defence ministry building; the executive council and their residences; the highways cluttered with protesters, police, teargas and the detritus of the biker gangs and their battles; the various sewer systems and public waterways; and of course the top-secret cryogenic storage facility underneath the Olympic Stadium which is where much of the climactic action at the end takes place.

Akira is often taken to be a critical commentary on transhumanism, and there is certainly this element to it. But its primary point is political. The powers that Tetsuo manifests are of interest to all of these duelling factions in Neo-Tôkyô: the politicians, the military, the scientists, the radicals and the millenarian religious sects – precisely because even though they are fundamentally creative (as the film’s coda implies for us), they manifest as the powers of destruction, of violent force. And, as Ôtomo very deftly tries to show us: look what happens when such powers are placed in the hands of a troubled young boy with an inferiority complex. Now imagine those same powers in the hands of a callous fascist like Shikishima, an amoral Dr Ônishi, or one of the various assorted religious zealots who end up rubbernecking after Tetsuo into his one-boy battle against the army. Let alone the various assortment of venial, squabbling liberal politicians in the executive council. In the immortal words of Shikishima at the start of his coup d’état:

Open up your eyes and look at the big picture; you’re all puppets of corrupt politicians and capitalists. Don’t you understand, it's utterly pointless to fight each other!

Ôtomo goes to some lengths to show us the sorts of forces that have made Tetsuo who he is, and also the fact that once before the awakening of his powers – and a second time after he begins to transform into a monstrous cybernetic ‘amœba’ (but again shows empathy for Kaneda and, alas belatedly, for his girlfriend Kaori) – Tetsuo is really kind of ‘normal’ and sympathetic. Because it’s not just the biker gangs that exert their force on him. It’s also the playground bullies in his childhood from whom Kaneda saved him. It’s the fact that Kaneda saved him as well, which – although he meant well – Tetsuo still resents because it robs him of control over his own life. It’s also the remedial-slash-vocational public school Tetsuo goes to, where we get to see the teachers routinely tell Tetsuo, Kaneda, Kai, Yamagata and the others that they’re scum who won’t amount to anything, and where we see discipline enforced with the open fist of the phys-ed teacher while the principal looks blandly on. Once they graduate, it becomes clear that they will be flung into a world where a handful of well-connected people own everything, and they get to look forward to a life kicking between unemployment and wage slavery in the Neo Tôkyô slums, under a government that clearly doesn’t give a rat’s ass about them.

Little wonder the logic of the biker gangs’ world is that of dog-eat-dog, or that it resembles the ‘brotherhood’ of Brat or Bumer! And little wonder that the first thing Tetsuo learns to do with his powers is use them to savagely dismember those he suddenly finds to be weaker than him. It’s small help to Tetsuo that millenarian religious fundamentalists who worship Akira begin cheering him on, proclaiming his powers as divine judgement against sinful mankind, as he begins his destructive rampage across Neo Tôkyô to the Olympic Stadium.

Insofar as transhumanism manifests as a will to power, a libido dominandi, a desire to control or subjugate or destroy life, then yes – Ôtomo is utterly unsparing in his critique, and leaves no doubt as to his belief that the crooked timber of humanity cannot build anything straight by becoming something other than human. But to get an idea of where and how Ôtomo could possibly trust human beings with such great power, we have to look to Akira’s fellow psionic test subjects: Takashi, Masaru and Kiyoko – as well as to Kei, who selflessly allows her body and consciousness to be used as the test subjects’ weapon during the final confrontation with Tetsuo. Here Ôtomo’s class politics and clear leftist preferences come into play again. We first see Kei among the protesters in the anti-austerity march at the beginning of the film, and based on her initially (but not implacably!) cold interactions with Kaneda we can see that her radical-left politics tend to be the overriding concern in her life. (Most of) the fellow radicals in her cell, who are trying to save the test subjects and expose the psionics research project to the public, are clearly willing to lay down their lives in defence of Takashi.

And the three psychic children as well – though they clearly scare the daylights out of Tetsuo at first – never intentionally use their powers to harm anyone. At the end, they join their powers together and sacrifice themselves to save Kaneda from being swallowed up in the singularity triggered by Akira’s power. It is in this bottom-up, coöperative collectivism, and in this will to self-sacrificial love, that Ôtomo ultimately places his trust, however ambiguous and conditional. It is only after this collective self-sacrifice by the test subjects that Akira’s power is manifested as something creative rather than merely a force for death and destruction. It’s strongly hinted that it’s only because of this collective self-sacrifice that a new world – a new cosmos – is literally created.

Akira is one of those anime films that ought to be essential (age-appropriate, of course) viewing for any serious fan of the medium. It’s rich. It’s complex. It’s visually gorgeous – even at its most grotesque. It’s imposing. It’s challenging. It’s politically profound. It literally birthed, and set the high bar for, an entire subgenre of Japanese animation whose heyday lasted over a decade and a half. It’s one of those films that manages to speak to us as meaningfully now as when it was first made in 1988. It continues to present to us the problem of human potential, and its hard limits in the face of persisting political and economic inequities.

Comments

Post a Comment